Pretend you are a corn farmer, and it is time to sow your seeds.

It’s spring, and it’s time to plant seed corn for the yearly crop. The government shows up and offers you a proposition: You can pay taxes now at a meager rate on just the seed corn, or you can wait until the harvest and pay taxes than on the full harvest, all of the kernels on all of the ears of corn on all of the stalks – and, oh, by the way, tax rates are going up before the harvest begins.

How much are they going up between now and the harvest? Well, who knows, but probably a whole lot. Now, which sounds like a better deal? Upon hearing this scenario, almost everyone would choose to pay their taxes on just the seed and be forever done with taxation, and yet they behave in the exact opposite manner.

You see, investing in a pre-tax 401(k) is similar to paying your taxes on the whole harvest of corn. You get a tax break when you contribute (the seed corn) to your 401(k), and it grows tax-deferred. When you withdraw money in your retirement years (the harvest), the tax rate you pay on the money coming out will likely be considerably higher than today’s tax rates. What makes me think that?

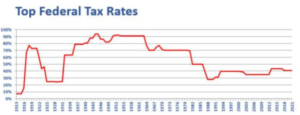

Well, the first reason is quite simple: it may not feel like it, but tax rates right now are near historic lows, so it’s only logical that they’ll go back up in the future, especially given the long time horizon of retirement. A look at the graph below will show you that higher tax rates are the rule, not the exception.

Then there’s the unbelievable, breathtaking, staggering national debt.

Right now, the debt is over $28 trillion, and, as bad as that is, it’s a drop in the bucket: we have $160 trillion in unfunded liabilities between Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the public sector pensions. For every dollar spent, there was a decision made that it will be taxed; it’s just a matter of when. The answer in American politics is almost always “later.” At some point, all of these liabilities need to begin being repaid, and by some estimates, tax rates could double or even triple. If you ever want to see some sobering numbers, visit usdebtclock.org, and you’ll see just how out-of-control our national finances have spiraled.

The final reason that your tax rate might be higher in retirement than now is that you will probably lose most (all?) of your deductions: the kids are long gone (no child tax credit), the house is paid off (no interest deduction), and seniors tend to increase their charitable giving by volunteering more time rather than more money (less philanthropic deductions).

For these reasons, you will likely pay a higher tax rate in retirement than you’re paying right now. That certainly sounds depressing, but fortunately, it’s avoidable. The government only gets one shot at taxing your money, so would you rather them tax the teeny, tiny seeds or the monstrous harvest? Most people will say “the seed.”